Formaldehyde in Your Home: What you need to know

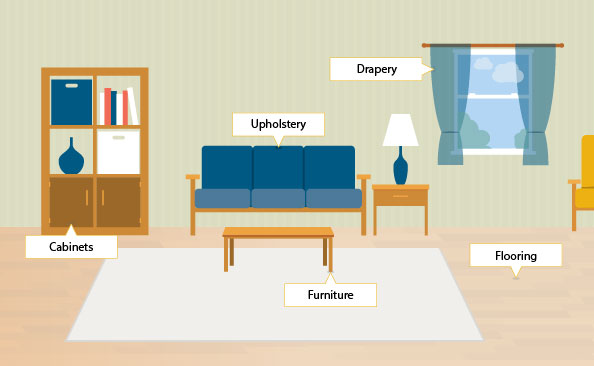

Formaldehyde is a chemical used in some building materials and household products like flooring, furniture, and fabric.

Coming into contact with (breathing in or touching) formaldehyde may affect your health. Protect your health by reducing the levels of formaldehyde in your home.

How can I know if my home has unhealthy formaldehyde levels?

There are small amounts of formaldehyde in nearly all homes.

Formaldehyde levels are higher in

- Homes with smokers. Tobacco smoke contains formaldehyde. If someone in your home smokes tobacco products, the smoke may be the greatest source of formaldehyde in your home.

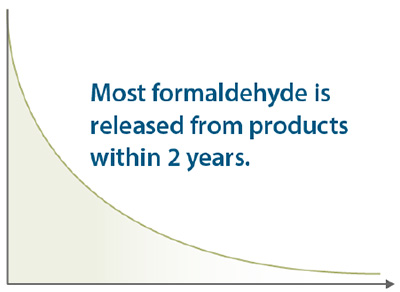

- Homes with new products or new construction. Formaldehyde levels are higher in new manufactured wood products such as flooring and furniture. Formaldehyde can also be found in some fabrics.

New products that often contain high levels of formaldehyde include

- Some manufactured wood products such as cabinets, furniture, plywood, particleboard, and laminate flooring

- Permanent press fabrics (like those used for curtains and drapes or on furniture)

- Household products such as glues, paints, caulks, pesticides, cosmetics, and detergents. See the Household Products Database for specific products containing formaldehyde http://hpd.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/household/search?tbl=TblChemicals&queryx=50-00-0external icon

-

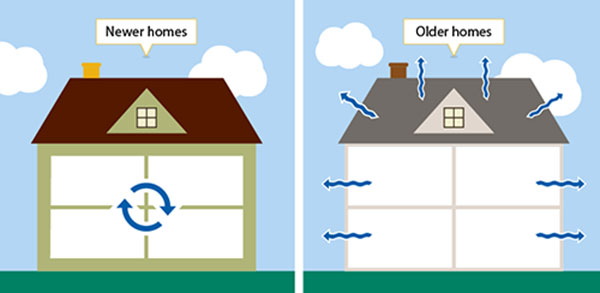

Homes built after 1990. Newer homes are better insulated, so less air is moving into and out of the home. Less air movement can cause formaldehyde to stay in the home’s air longer [Persily et al. 2010].

Formaldehyde is also found in gas stoves, open fireplaces, and outdoor air pollution.

How can I lower levels of formaldehyde in my home?

You can lower the amount of formaldehyde in your home by taking the following steps:

Reduce formaldehyde already in the home.

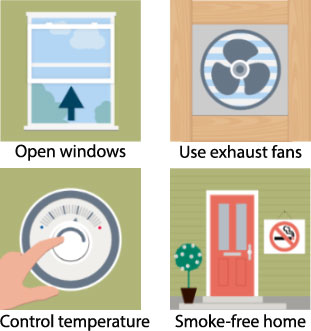

- Open windows for a few minutes every few days to let in fresh air — unless you have asthma triggered by outdoor air pollution or pollen or you’re concerned about safety.

- Install and use exhaust fans as much as possible.

- Keep the temperature and humidity inside your home at the lowest comfortable setting.

- Make your home smoke free. Don’t allow anyone to smoke in your home.

Choose home products with low or no formaldehyde for future purchases. Look for

- Furniture, wood cabinetry, or flooring made without urea-formaldehyde (UF) glues

- Pressed-wood products that meet ultra-low emitting formaldehyde (ULEF) or no added formaldehyde (NAF) requirements

- Products labeled “No VOC/Low VOC” (volatile organic compound)

- Insulation that does not have UF foam

Reduce formaldehyde from new products.

- Wash permanent-press clothing and curtains before using them.

- Let new products release formaldehyde outside of your living space before you install or use them inside, for example in a garage or on a patio. If possible, keep them out of your living space until you can no longer smell a chemical odor.

Note: Air filters generally don’t help lower levels of formaldehyde in your home. Overheating your home to “bake” out the formaldehyde also doesn’t work and may even raise formaldehyde levels.

How can formaldehyde in my home affect my health?

Most people don’t have any health problems from small amounts of formaldehyde in their homes. As levels increase, some people have breathing problems or irritation of the eyes, nose, throat, or skin from formaldehyde exposure in their homes.

These health effects can happen in anyone, but children, older adults, and people with asthma and other breathing problems are more likely to have these symptoms. If you or someone in your home has these symptoms, follow the steps to reduce indoor formaldehyde levels. If the symptoms continue, talk to a doctor about them.

Breathing in very high levels of formaldehyde over many years has been linked to rare nose and throat cancers in workers. Formaldehyde exposure from new products or new construction in the home would generally be much lower and would last for less time than the exposures linked to cancer. We estimated the risk of cancer from exposure to typical indoor air levels and it’s low.

When should I get my home tested for formaldehyde?

You don’t need to consider getting your home tested unless

- You can still smell strong chemical odors

OR - You have symptoms like breathing problems and irritation only when you’re in your home.

If you want to test your home, hire a qualified professional who has the training and equipment to test formaldehyde levels in your home. Note that these tests can be expensive and don’t tell you which products are releasing the most formaldehyde in your home.

There are some tests you can do yourself, but results from these home-testing kits can be different based on where you take the air samples and how long you do the testing. You might not be able to compare home testing results to the results of tests done by qualified professionals.

When the results come in, you can talk with the professional about what to do next. Keep in mind that there are no standards for acceptable levels of formaldehyde in your home.

Where can I get more information?

- You can contact CDC/ATSDR for updated information at 1-800-CDC-INFO.

- If you have questions or concerns about the products used in your home, contact the Consumer Product Safety Commission at 1-800-638-2772.

- For more information on , indoor air quality, and laminate flooring, visit https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/laminateflooring/default.html

References:

Park J. and Ikeda R. 2006. Variations of formaldehyde and VOC levels during 3 years in new and older homes. Indoor Air. 16:129–135.

Persily A., Musser A., Emmerich S. 2010. Modeled infiltration rate distributions for U.S. housing. Indoor Air. 20(6): 473-485.