2016 DCHI Annual Report

Using State of the Art Science to Protect American Communities

As a division of the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), we at the Division of Community Health Investigations (DCHI) work to protect Americans from the dangerous health effects of toxic substances in their environment. We respond to requests from federal, state, and local government environmental agencies and communities.

Every year, we work with communities around the country to find out if people in those communities are coming into contact with hazardous chemicals where they live, work, learn, and play. When dangerous conditions exist, we partner with the community, as well as other public health and regulatory agencies, to implement solutions that will prevent harmful exposures and protect public health.

In 2016, ATSDR responded to over 520 requests, investigating the potential health risks of nearly 950,000 people in 35 states and territories. Our work resulted in actions that protected people from serious environmental threats – including exposure to dangerous levels of asbestos, lead, mercury, arsenic, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and other toxic substances.

RESPOND

It starts with an invitation. When faced with a possible environmental threat, community organizations and environmental agencies can request DCHI’s assistance investigating and responding to that threat. In 2016 we responded to over 520 requests made across the country.

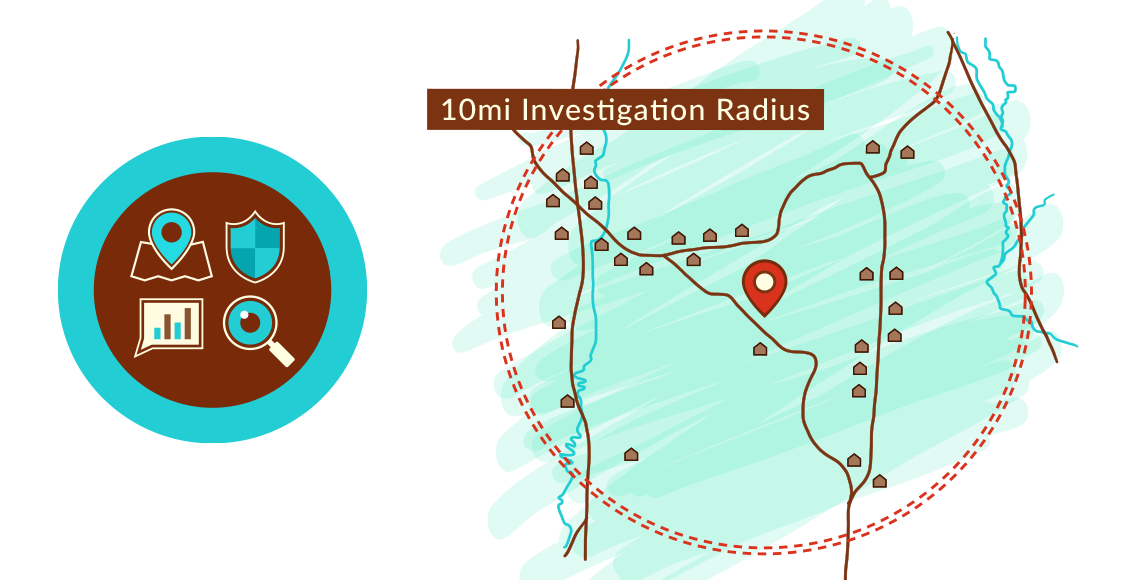

INVESTIGATE

DCHI’s investigations can range from assessments of only a handful of people to 100,000 or more. Not everyone who might be exposed to a toxic substance will suffer the health effects caused by an exposure – but many do. Of the nearly 950k individuals DCHI assessed in 2016, more than 230k were exposed to levels of contaminants that might be considered harmful.

PROTECT

We know that all communities have different needs. That’s why DCHI works closely with state and local organizations – as well as community members themselves – throughout our process. These partnerships help us create recommendations that are tailored to each community’s specific needs and best able to safeguard the people living and working there. In 2016, DCHI worked with 130 communities, and helped protect nearly 100,000 people from harmful exposure.

Prevent

But our work doesn’t stop when an environmental threat is contained. In order to ensure the sustainability of prevention and protection efforts, DCHI helps empower communities to better protect themselves.

We're on the move

In 2016, DCHI’s investigations took us from Florida to Alaska, coast to coast, and almost everywhere in between.

States Snapshot

For highlights from DCHI’s investigations in 2016, choose a state or territory from the dropdown below.

States where DCHI conducted investigations

States where DCHI conducted investigations States funded by DCHI to address exposures

States funded by DCHI to address exposures States not funded by DCHI and where no DCHI investigations occurred

States not funded by DCHI and where no DCHI investigations occurred

National “No Tresspassing” Campaign

In 2016 DCHI, launched an award-winning “No Trespassing” Initiative to inform tweens and their parents about the dangers of trespassing on hazardous sites or playing around abandoned facilities.

To reach its target audience, DCHI released the PSA on YouTube and partnered with Channel One, a daily television newscast that is shown to 12,000 middle, junior, and senior high school students.

Environmental hazards come in many forms, from familiar dangers like arsenic and lead, to lesser-known toxins such as Trichloroethylene (TCE) and Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). These toxic substances all have one thing in common: their ability to cause serious, long-term health problems and even death. The case studies below describe just a handful of the environmental hazards and toxic substances we helped communities tackle in 2016 – and highlight some of the state-of-the-art techniques and innovative community-based solutions DCHI’s staff brought to each case.

Arsenic

Heavy metals and organic materials commonly contaminate urban soils.

Arsenic can effect almost every organ system in the body, including the brain; children are especially at risk.

Acute arsenic poisoning can cause vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, numbness and tingling of the extremities, muscle cramping, and, in extreme cases, death.

Long-term exposure to arsenic can cause cancer and may be associated with developmental effects, neurotoxicity, diabetes, pulmonary disease and cardiovascular disease.

DCHI helped at-risk urban gardens

In Philadelphia, New York City, and other major U.S. cities, a new hobby called urban gardening gathered momentum in apartments, residential homes, school, and other places in the hearts of the cities. The great idea of urban gardening, however, does come with risks. But with proper guidance, urban gardening provides a fun, healthy, and rewarding alternate to going to the grocery store.

SoilSHOP Initiative

ATSDR worked with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and a group of artists called Futurefarmers to create an environmental art exhibit called “Soil Kitchen” (later expanded and renamed “soilSHOP” [Soil Screening, Health, Outreach, and Partnership])

ATSDR continues to participate in soilSHOPs to engage and inform residents about potential health hazards and give recommendations as to how residents can prevent exposures.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2010, January 15). Environmental Health and Medicine Education. Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/arsenic/physiologic_effects.html

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2015, January 21). Toxic Substances Portal - Arsenic. Retrieved from https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/PHS/PHS.aspx?phsid=18&toxid=3

- World Health Organization. (2016, June). Arsenic. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs372/en/external icon

- Tyler, C. R., & Allan, A. M. (2014, March 21). The Effects of Arsenic Exposure on Neurological and Cognitive Dysfunction in Human and Rodent Studies: A Review. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4026128/external icon

Lead

Lead can affect almost every organ and system in your body, yet lead exposure often occurs without obvious symptoms and can go unrecognized.

High levels of lead exposure can severely damage the brain and kidneys in adults or children and ultimately cause death.

Lead enters the body by breathing contaminated air or dust, eating contaminated foods, or drinking contaminated water.

Children are more vulnerable to lead poisoning than adults. Even at much lower levels of exposure, lead can affect a child's mental and physical growth.

Since the 1920’s, the tidal marshes of the LCP Chemical site, located north of Brunswick, Georgia, has been contaminated by toxic industrial waste. Among the many contaminants, investigators found PCBs, hydrocarbons, and heavy metals, including mercury, arsenic, and lead. These contaminants poison the dolphins in the nearby Turtle River and the fish in the marshes.

DCHI partnered with local, state, and federal agencies to address community concerns, as locals expressed dissatisfaction with the EPA’s proposed plan of cleanup activities. In response, DCHI and its partners planned regular community meetings, offered contaminant testing services, provided health education to vulnerable populations, and produced fish consumption guidelines for the Turtle River.

- World Health Organization. (2016, September). Lead poisoning and health. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs379/en/external icon

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2016, August 25). Environmental Health and Medicine Education. Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/leadtoxicity/physiological_effects.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013, September 30). Lead. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/lead/health.html

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2017, March 02). Learn about Lead. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/lead/learn-about-leadexternal icon

- National Institute of Environmental Health Services. (2017, February 22). Lead. Retrieved from https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/lead/external icon

Mercury

Elemental mercury exposure can happen in the home through household items or contaminated items.

Mercury is absorbed into the body most readily as a vapor in the air; when it is ingested or passes through the skin, it has less ability to harm you.

Mercury has both long term and short term effects, including problems with vision, numbness, loss of coordination, or speech impairment.

Fetal exposure to mercury or methylmercury in the womb can lead to cognitive defects.

Flooding after a heavy rainstorm in Arizona in 2015 released mercury from the subfloors of several school gymnasiums. The mercury was used as an ingredient in the production of a type of subflooring known as ‘Tartan’, and was breaking down and vaporizing into the school gyms. As a result, air from the gym was traveling through the ventilation systems into the rest of the rooms, contaminating the entire building.

The Arizona School Facilities Board (SFB) needed to act fast. In partnership with the Arizona Department of Health Services (ADHS) and the ATSDR, the Arizona SFB assessed 168 schools’ floors in 154 schools through two rounds of investigations. ADHS and ATSDR worked together to conduct air quality monitoring and risk assessments and provide information about mercury vapor and children’s health to parents and the concerned public. Arizona’s proactive and comprehensive approach allowed collaboration with multiple agencies. Communication between the state, the agencies, and the public flowed effortlessly, and together with its partners, ATSDR was able to protect and educate these communities.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2015, November 24). Mercury Quick Facts: Health Effects of Mercury. Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/mercury/docs/healtheffectsmercury.pdfpdf icon[PDF - 432 KB]

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2017, March 30). Health Effects of Exposures to Mercury. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/mercury/health-effects-exposures-mercuryexternal icon

- World Health Organization. (2017, March). Mercury and health. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs361/en/external icon

- Rice, K. M., Walker, E. M., Wu, M., Gillette, C., & Blough, E. R. (2014, March 31). Environmental Mercury and Its Toxic Effects. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3988285/external icon

- Azevedo, B. F., Furieri, L. B., Peçanha, F. M., Wiggers, G. A., Vassallo, P. F., Simões, M. R., . . . Vassallo, D. V. (2012, July 2). Toxic Effects of Mercury on the Cardiovascular and Central Nervous Systems. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3395437/external icon

Air Pollution

Air pollution, also referred to as particulate matter is a complex mixture of extremely small particles and/or liquid droplets coming from areas polluted by toxic substances.

Particles cause serious health effects by getting into the bloodstream or the lungs.

Particles travel long distances from their source, carried by wind, creating haze in our parks, damaging our crops, and harming our health.

Particulate matter exposure is linked to premature death in people with heart or lung disease, nonfatal heart attacks, irregular heartbeat, aggravated asthma, decreased lung function, and increased respiratory problems.

In June 2015, Brooklyn Township residents had had enough of the negative health effects of particulate matter from natural gas drilling and distribution. The residents of the beautiful rural Pennsylvania town had experienced poor air quality that caused upper respiratory tract irritations, including sore throats, headaches, and bloody noses. They requested assistance from the Pennsylvania Department of Health (PADOH), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), PADEP, and ATSDR.

ATSDR is responsible for investigating health hazards and protecting health, and engages communities, like Brooklyn Township, who experience exposure and effects of exposure to toxic substances across the nation. ATSDR works with the community and other agencies to identify, investigate, address, and eliminate health threats and protect residents’ health. In Brooklyn Township, ATSDR recommended actions that residents could take to protect their health and made recommendations to local and state authorities on what needed to be done to reduce these harmful particles.

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2016, July 01). Health and Environmental Effects of Particulate Matter (PM). Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/health-and-environmental-effects-particulate-matter-pmexternal icon

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, July 22). Particle Pollution. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/air/particulate_matter.html

TCE

Trichloroethylene (TCE) is a common industrial solvent from hazardous waste sites that can contaminate groundwater, soil, air, and drinking water.

TCE contaminated water and air, acting as a suspected hepatotoxin and carcinogen when people drink contaminated water or inhale TCE-contaminated water vapor.

Exposure to moderate levels of TCE may cause headaches, dizziness, sleepiness.

Exposure to high levels of TCE can cause skin rashes, change heart rhythms, cause liver, kidney, and nerve damage, coma and even death.

In the small town of Waycross, GA, residents voiced concern over their drinking water because of hazardous waste from two large industrial sites, an old rail yard and a former gas plant (est. 1916). Train brake degreasers containing TCE and tar by-products from the gas plant containing cancer-causing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) had permeated the area. In 2015, panic heightened when four children in the community were diagnosed with a rare childhood cancer.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) arrived in Waycross in early 2016 to investigate the hazards. In partnership with the Georgia Department of Public Health (DPH), ATSDR gathered data, evaluated exposures, and investigated health impact. At a public meeting, scientists answered questions and clarified residents’ concerns. Contrary to common belief, TCE was not leaching into local aquifers or contaminating drinking water, but was present in the air and upper layer of soil. ATSDR oversaw cleanup of the area, using an “air stripper” to remove TCE evaporating from the ground. Throughout the investigation and cleanup, ATSDR kept the public informed and involved, ultimately bringing peace to a community in panic.

- Chiu, W. A., Jinot, J., Scott, C. S., Makris, S. L., Cooper, G. S., Dzubow, R. C., . . . Caldwell, J. C. (2013, December 8). Human Health Effects of Trichloroethylene: Key Findings and Scientific Issues. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3621199/external icon

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2013, December 10). Environmental Health and Medicine Education. Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/trichloroethylene/physiological_effects.html

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2015, January 21). Toxic Substances Portal - Trichloroethylene (TCE). Retrieved from https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/PHS/PHS.aspx?phsid=171&toxid=30

PFAS

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) are a large group of man-made chemicals that have been used in industry and consumer products worldwide since the 1950s.

Some PFAS accumulate in the human body and degrade very slowly over time.

Chronic exposure has been shown to lead to the development of testicular, pancreatic, and liver cancers in animals. (EPA)

All possible health effects resulting from human exposure to PFAS at levels typically found in our water and food are still being studied.

In 2010 people in and around Decatur, Alabama, who lived near or downstream of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) producing facilities, were concerned about possible PFAS exposure in their water. These facilities used PFAS to make industry and consumer products because they are resistant to heat, oil, grease, and water, but may have been harming the people around them in making their products. ATSDR responded to community concerns, tested people for exposure, and found elevated blood levels of PFAS.

ATSDR maintained relationships with Decatur for six years, returning in 2016 to investigate the efficacy of protection efforts. While ATSDR was able to confirm that PFAS exposure was less, they discovered that community was able to place their trust in efforts by the government to rectify contamination and to protect human health. This provided a powerful signal to local, state, and federal officials to work harder for the trust and health of the people.

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2016, July 26). Basic Information about Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/pfas/basic-information-about-and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfassexternal icon

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2016, September 19). Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Your Health. Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfc/