Clinical Assessment – Diagnostic Tests and Imaging

Upon completion of this section, you will be able to

- Describe guidelines for blood lead screening and confirmatory diagnostic testing on patients at risk of recent or ongoing lead exposure, and

- Describe imaging and other clinical modalities that may assist in the diagnosis of current or past lead exposed patients.

If lead exposure is suspected, a blood lead level (BLL) test should be performed.

Oftentimes, recognition of lead exposure doesn’t occur until the initial reporting of high blood lead levels (BLLs) by primary care providers.

In 1991, CDC recommended universal blood lead level (BLL) testing for all children, in the absence of a statewide or local plan.

Over the past 40 years, there has been a dramatic decline in the United States in BLLs. Findings from the most recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2007 – 2010, indicate that BLLs are continuing to decrease across all age and racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Despite progress in reducing BLLs among children overall, differences between the geometric mean (GM) BLLs of different racial/ethnic and income groups still persist.

Based on the prevalence of elevated BLLs, local health departments or other relevant agencies may implement different testing guidelines, such as screening more frequently or at different ages.

The Advisory Committee On Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention [ACCLPP 2012] recommends that health care providers:

- Follow local and state lead screening guidelines,

- Screen children coming from other countries when they arrive in the United States, and

- Screen neonates and infants born to women with lead exposure during pregnancy and lactation per earlier CDC guidance.

Some communities may provide screening outside of the child’s medical home (such as through the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program). It is not necessary for the clinician to duplicate those efforts, but he/she should verify that the screening was performed elsewhere before testing is deferred during the office visit.

Evidence continues to accrue that commonly encountered blood lead concentrations, even those below 5 μg/dL (50 ppb), impair cognition [AAP 2016]. There is no identified threshold or safe level of lead in blood [AAP 2016, ACCLPP 2012].

Over the past several decades there has been a remarkable reduction in environmental sources of lead, improved protection from occupational lead exposure, and an overall decreasing trend in the prevalence of elevated BLLs in U.S. adults. As a result, the U.S. national BLL geometric mean among adults was 1.2 μg/dL during 2009-2010 [CDC 2013i]. The OSHA lead standard allows blood lead levels higher than what is currently recommended by CDC/NIOSH. Therefore, some workers may continue to experience elevated blood lead levels.

A 2005 guidance statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP 2005] summarized the history of lead screening and suggested that pediatricians screen according to local and state guidelines where they apply. Additionally, pediatricians should screen:

- All non-Medicaid children in the absence of local and state guidelines, and

- All immigrant, refugee, and internationally-adopted children when they arrive in the United States (regardless of age), due to their increased risk, as they may have been exposed to lead in their country of origin.

In 2009 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the CDC recommended that local officials have the flexibility to develop lead screening strategies that reflect local risk for high blood lead levels. In 2013 CMS published guidelines for states interested in transitioning to targeted blood lead screening for Medicare/Medicaid eligible children.

In addition to a national surveillance program, clinical testing for lead exposure must continue for the foreseeable future in order to identify those children for whom primary prevention measures have failed [ACCLPP 2012].

- BLL testing is currently required at 12 and 24 months for all Medicaid-enrolled children, unless the state has a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CDC/CMS) waiver indicating that children enrolled in Medicaid are not at higher risk for high BLLs than other children.

- Testing will often occur during routine well-child care as recommended by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the American Academy of Pediatricians (AAP).

- Children ≤72 months that missed recommended screening at a younger age should be screened at presentation.

- Screening at 12 and 24 months satisfies the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures.

The CDC [2010] also recommends initial and follow-up screening of pregnant and lactating women, as well as for neonates and infants of women with BLLs ≥5 micrograms per deciliter (µg/dL).

Different tests have been used in the past to evaluate lead exposure and/or to gauge the effects of lead exposure.

- Venous BLL testing is the most useful screening and diagnostic test for recent or ongoing lead exposure [ACCLPP 2012], and requires a phlebotomist trained in the specific methods and techniques involved with proper collection and processing of a specimen for blood lead level testing (to avoid lead contamination of the puncture site or the sample).

- Direct measurement of lead in capillary blood samples are easier to collect, but have a high potential for lead contamination [CDC 1997a]. For this reason, this method is not recommended unless the collection method used, close attention to hand washing, and other strategies to reduce lead contamination are strictly followed. Confirmatory testing using a venous blood lead sample for all capillary and venous BLL results greater than or equal to the reference value should be performed [ACCLPP 2012].

- BLLs respond relatively rapidly to abrupt or intermittent changes in lead intake (for example, ingestion of higher lead content paint chips by children) and, for relatively short exposure periods, bear a linear relationship to those intake levels.

- For individuals with high or chronic past exposure, however, BLLs often under-represent the total body burden because most lead is stored in the bone. Individuals can therefore have high body burden of lead with “normal” levels in the blood.

- One exception is patients with a high body burden under physiological stressful circumstances whose BLLs may be elevated from the release of lead stored in bones.

- Erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP), commonly assayed as zinc protoporphyrin (ZPP), was previously considered the best test for screening asymptomatic children for lead exposure. However, it is not sufficiently sensitive at lower BLLs and therefore not as useful for screening as previously believed.

- Hemoglobin (Hgb) screening was recommended in the past; however, if performed alone it is only sufficient to diagnose anemia (by definition), and does not specifically rule out iron deficiency

BLLs are continuing to decrease across all age and racial/ethnic groups in the United States.

- The average BLL for children 1-5 years of age was 1.9 µg/dL in 2002, down from 15.0 µg/dL in 19761980 (before leaded gasoline was banned for use in “on road” vehicles) [CDC 2005].

- The average BLL for adults 18-74 years of age was 14.2 µg/dL from 1976-80; in 1988-1991, the average BLL for adults was 3.0 µg/dL [CDC 1997b]; and the BLL geometric mean among adults was 1.2 µg/dL during 2009-2010 [CDC 2014].

- The difference between the geometric mean (GM) BLL of non-Hispanic black children (1.8 µg/dL) remains significant (p<0.01) compared with either non-Hispanic white (1.3 µg/dL) or Mexican American (1.3 µg/dL) children [CDC 2013h].

- Children belonging to families with a poverty income ratio (PIR) <1.3 have a significant GM BLL difference (1.6 µg/dL versus 1.2 µg/dL [p<0.01]), compared to families with a PIR ≥1.3. This also applies to those enrolled in Medicaid [CDC 2013h].

Current research continues to find that BLLs previously considered harmless can have harmful effects in adults, such as decreased renal function and increased risk for hypertension and essential tremor at BLLs <10 µg/dL.

In 2015, NIOSH designated 5 µg/dL (five micrograms per deciliter) of whole blood, in a venous blood sample, as the reference blood lead level for adults [CDC 2013h]. An elevated BLL is defined as a BLL ≥5 µg/dL. This case definition is used by the CDC’s Adult Blood Lead Epidemiology and Surveillance program (ABLES tracks elevated BLLs among adults in the United States), the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE), and CDC’s National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). Previously (i.e., from 2009 until November 2015), the case definition for an elevated BLL was a BLL ≥10 µg/dL. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends that BLLs among all adults be reduced to <10 µg/dL.

During 2002-2011, ABLES identified 11,536 adults with very high BLLs (≥40 µg/dL). A very high BLL measured in >1 calendar year was defined as a persistent very high BLL. Among these adults, 2,210 (19%) had persistent very high BLLs, 1,487 (13%) had BLLs ≥60 µg/dL, and 96 had BLLs ≥60 µg/dL in >1 calendar year. Occupational exposures accounted for 7,076 adults with very high BLLs (91% of adults with known exposure source) and 1,496 adults with persistent very high BLLs [CDC 2013h].

In contrast to the CDC reference level, prevailing Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) lead standards allow workers removed from lead exposure to return to lead work when their BLL falls below 40 µg/dL. However, NIOSH recommends that the most current guidelines for management of lead exposed adults be implemented by the medical community at the current CDC/NIOSH reference BLL of 5 µg/dL [CDC 2013h].

The finding that many workers may have harmful BLLs, some that are present for >1 calendar year, is of grave concern. Adverse health effects associated with very high BLLs underscore the need for increased efforts to prevent lead exposure at workplaces and in communities [CDC 2013i]. An attempt should be made to identify and minimize lead exposures when BLLs indicate that they are occurring at any blood lead level above background population levels.

If an adult has a BLL of 20 µg/dL, e.g., an unusual exposure is likely occurring and should be interrupted, if possible. This is especially important for fertile and pregnant females.

Given the uncertainty of individual blood lead test results, it is important to do confirmatory testing, especially for capillary blood samples that might be elevated due to residual lead on the skin at the puncture site. Collection tubes need to be confirmed “lead free”. The recommended schedule for confirmatory testing is summarized in Table 7 and includes

- All capillary and venous BLL results greater than or equal to the reference value must be confirmed within 1-3 months, and

- Children with BLLs ≥45 µg/dL or with symptoms of lead poisoning should have an immediate (within 48 hours) confirmatory test.

Table 7. Recommended Schedule for Obtaining a Confirmatory Venous Sample

| Blood Lead µg/dL | Time to Confirmation Testing |

|---|---|

| ≤ Reference value of 5* | 1-3 months |

| 6-44** | 1 week – 1 month |

| 45-59 | 48 hours |

| 60-69 | 24 hours |

| ≥70 | Urgently as emergency test |

*ACCLPP 2012

**The higher the BLL on the screening test, the more urgent the need for confirmatory testing.

Adapted and updated from: Screening Young Children for Lead Poisoning: Guidance for State and Local Public Health Officials [CDC 1997a].

Response actions should be initiated only after elevated BLLs are confirmed.

There are different clinical modalities available to further evaluate patients with elevated BLLs.

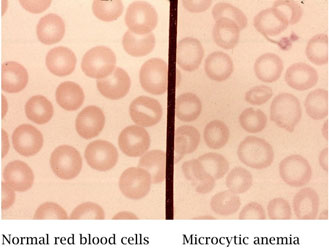

- Complete blood count (CBC) may be useful for patients with extensive lead exposure. In lead-exposed patients, the hematocrit and hemoglobin values may be slightly to moderately low in the CBC, and the peripheral smear may be either normochromic and normocytic or hypochromic and microcytic.

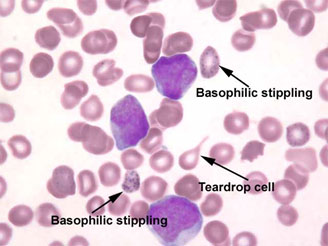

- There may be basophilic stippling in patients who have been significantly poisoned for a prolonged period.

- However, because these results are not specific to lead exposure, the CBC test is not as valuable for detecting lead exposure as the BLL and EP assays.

Figure 5. Basophilic stippling – Venous blood smear with basophilic stippling (Provided courtesy of ©Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health)

- A hypochromic, microcytic anemia should be appropriately differentiated from other causes, especially iron-deficiency anemia by the use of testing for iron, iron binding capacity, and ferritin.

Figure 6. Microcytic hypochromic anemia can be associated with lead poisoning (Public domain)

- Abdominal radiographs may show the presence of radiodense lead foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract. These are helpful in cases of acute ingestion (e.g., of lead sinkers, curtain weights, jewelry, or paint chips) or unusual persistence of high blood lead values. Shrapnel or bullet fragments within tissues can also be observed.

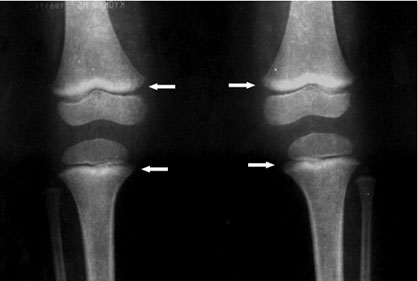

- Long bone radiographs can show “lead lines”. These are lines of increased density on the metaphysis (growth plate) of the bone, showing radiological growth retardation. This is not a routine procedure to identify lead poisoning, but a radiological finding of chronic exposure.

- Long bone radiographs are not recommended for diagnosing lead exposure [CDC 2002], however, they are useful to determine growth retardation.

- Because hair and fingernails are subject to external environmental contamination, assaying their lead content is an uncertain estimate of body burden and is not recommended [AAP 1993; CDC 2002].

- Second tier tests (such as neurobehavioral/psychological evaluation for children with indicative findings on exam)should be considered, as appropriate.

Figure 7. Long Bone Radiograph of Hands – “lead lines” shown as increased density on the metaphysis (growth plate) of the proximal segments of phalanges and distal segments of ulna and radius in a 5-year-old male with radiological growth retardation and BLL of 37.7 µg/dL (Photo courtesy of Dr. Celsa López, Clinical Epidemiologic Research Unit, IMSS, Torreón, México).

Figure 8. Long Bone Radiograph of Knees – “lead lines” in three-year old girl with BLL of 0.6 µg/dL. Notice the increased density on the metaphysis growth plate of the knee, especially in the femur (Photo courtesy of Dr. Celsa López, Clinical Epidemiologic Research Unit, IMSS, Torreón, México).

- The best screening and confirmatory diagnostic tool for evaluating recent or ongoing lead exposure is the venous BLL test.

- Pediatricians should screen for lead in all non-Medicaid children in the absence of local and state guidelines.

- All immigrant, refugee, and internationally-adopted children should be screened for lead when they arrive in the United States.

- Pregnant and lactating women should be screened for lead.

- The CDC (2012) has updated the blood lead reference value to 5 μg/dL.

- Using an EP or ZPP assay to screen children for lead exposure is not as useful as once believed, and not recommended.

- Other tests may be appropriate for specific situations, such as abdominal radiographs to detect swallowed objects.

- Secondary testing/imaging for signs of other health effects may also be useful.