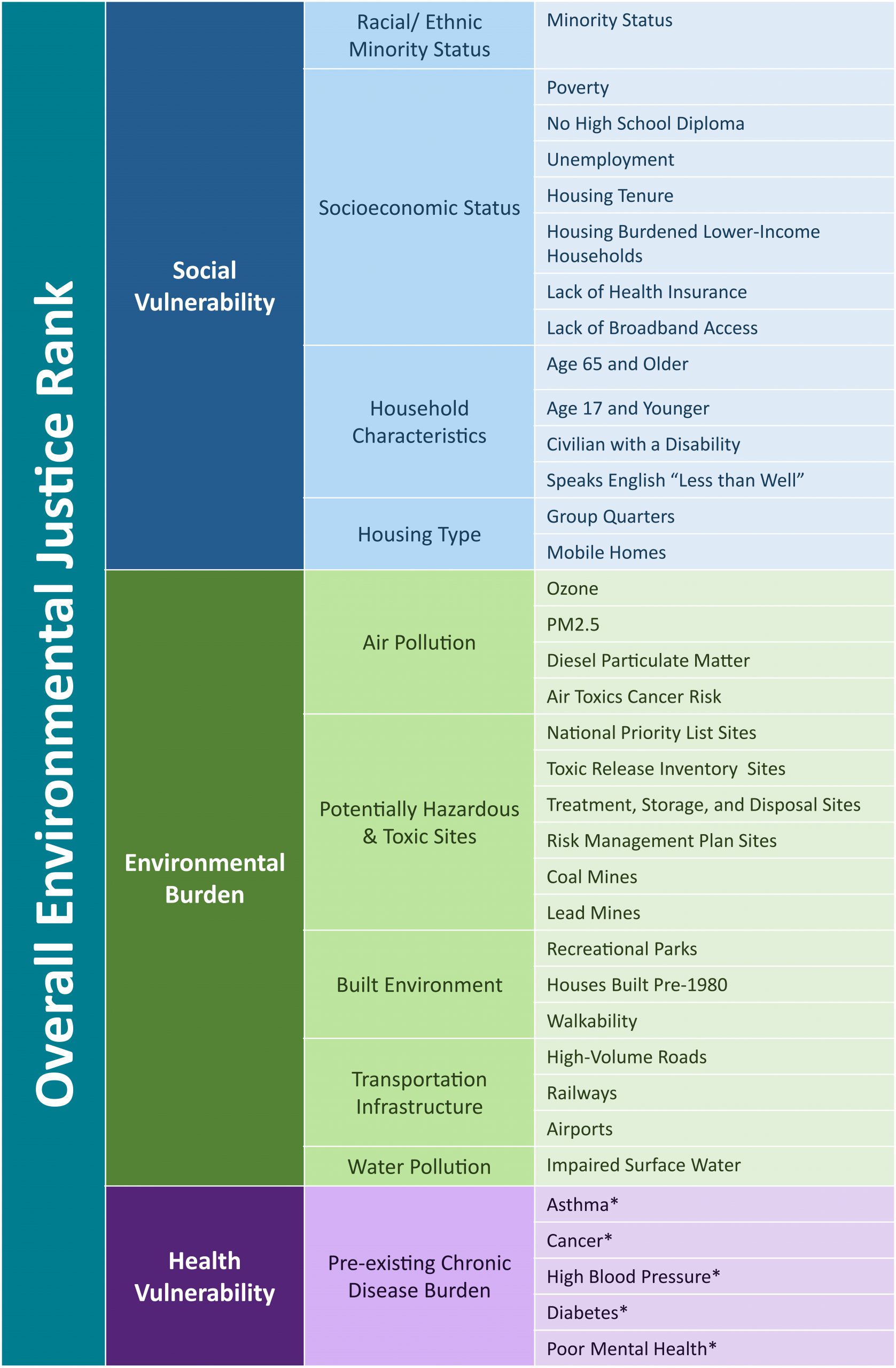

Environmental Justice Index Indicators

Learn more about the EJI indicators below.

Social Vulnerability Module

Indicator: Percent of population that is a racial/ethnic minority (all persons except white, non-Hispanic)

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

Historical and ongoing racial residential segregation, race-related income inequality, and other forms of institutional and systemic racism have often limited the ability of these populations to advocate against unwanted land uses or influence environmental decision-making, as borne out by the disproportionate location of contamination sites near non-white populations (Bullard et al., 2008; Cutter et al., 2003; Ernst, 1994; Lee, 1992). Systemic racism has been labeled by the CDC as a serious public health threat (see statement here: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s0408-racism-health.html). A growing body of data suggest that aspects of systemic and structural racism contribute to health disparities, including those associated with environmental pollution, through a number of pathways, including discrimination by the institutional medical system (Boateng & Aslakson, 2021). Minorities experiencing negative health effects associated with environmental pollution may experience barriers to accessing health care due to discrimination and other factors and may suffer disproportionately adverse outcomes (Neighbors et al., 2007; Smedley, 2012; Williams & Mohammed, 2009).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percent of population with income below 200% of federal poverty level

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

Poverty is an indication of economic hardship. Lack of financial resources may hinder a community’s ability to influence environmental decision-making, leading to contamination sites being disproportionately located in impoverished areas (Mohai & Bryant, 1991; Mohai & Saha, 2015; Tanzer et al., 2019). Low-income populations are also particularly susceptible to adverse health outcomes, at least in part due to psychosocial and chronic stress and lack of healthcare access (Evans & Kim, 2013; Haushofer & Fehr, 2014; Wright et al., 1998). Research indicates that negative effects of air pollution on birth outcomes are greater for mothers from low-income neighborhoods (Padula et al., 2014; Yi et al., 2010).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percent of population (age 25+) with no high school diploma

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

Educational attainment is an important factor of socioeconomic status and may influence communities’ ability to navigate information about pollution, environmental law, and community-scale resources to influence environmental decision-making (Helfand & Peyton, 1999). Education also influences populations’ susceptibility to health impacts of negative environmental conditions. Low educational attainment has been shown to be associated with increased risk of adverse birth outcomes (Gray et al., 2014; Thayamballi et al., 2021) and overall mortality (Kan et al., 2008).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percent of population age 16 and older who are unemployed

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

Unemployment is an important marker of community socioeconomic status. Lack of employment often means limited financial resources as well as decreased social capital due to stigma. These factors can reduce this population’s ability to influence environmental decision-making. Furthermore, fear of unemployment can prevent communities from advocating against unwanted land uses that provide employment opportunities (Bullard, 1993), and communities with high rates of unemployment may be more receptive to incoming industrial facilities that offer jobs, essentially trading employment for environmental pollution to avoid extreme poverty (Shrader-Frechette, 2002). Unemployment is also associated with stress and stress-related inflammation, potentially rendering these populations more vulnerable to health effects mediated by stress (Ala-Mursula et al., 2013; Dettenborn et al., 2010; Heikkala et al., 2020).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percent of housing units that are renter-occupied

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

Renters are often seen as more transitory and, thus, may have less social capital within the context of environmental decision-making, especially within the context of environmental efforts specifically geared towards homeowners who have vested rights and interests in defending local environmental quality and land values (Perkins et al., 2004; Shapiro, 2005). Additionally, research consistently supports the idea that renters experience worse health outcomes associated with a range of conditions when compared to homeowners, likely due to complex interactions between general socioeconomic status associated with housing tenure and aspects of the physical and meaning-based environments represented by rented and owned housing units (Hiscock et al., 2003; Mawhorter et al., 2021).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percent of households with annual income less than $75,000 who are considered burdened by housing costs (pay greater than 30% of monthly income on housing expenses)

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the U.S. Census Bureau define a household as “housing cost burdened” if that household pays greater than 30% of monthly income on housing costs. Housing costs represent a significant financial burden for most households, and populations burdened by housing costs and associated debt may lack financial resources or time to devote to improving environmental conditions. Additionally, research indicates that persons experiencing housing burden may be less likely to have access to preventative care or to postpone health care (Meltzer & Schwartz, 2016). Instability associated with housing cost burden can also exacerbate issues of stress and poor mental health and are correlated with worse developmental and educational outcomes for children (Burgard et al., 2012; Newman & Holupka, 2016; Suglia et al., 2011).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percent of civilian, noninstitutionalized population who have no health insurance

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

The total population of insured persons in the US has consistently declined since 1997, despite the recent uptick in 2018-2019, where about 11% of the population at the time remained uninsured. This population of uninsured persons are commonly of families with low income (with typically one person working in the family), people of color, and undocumented immigrants (Tolbert et al., 2020). Financial burdens associated with healthcare may the reduce uninsured populations’ ability to engage in the environmental decision-making process. Further, individuals without insurance have barriers to accessing preventative care following adverse environmental events, increasing risk of morbidity and mortality among uninsured populations (Mulchandani et al., 2019; Woolhandler & Himmelstein, 2017).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percent of households with no internet subscription

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

Lack of access to broadband services can impede populations’ ability to be engaged in decision-making and to be informed on environmental issues in their communities. The inability to access the internet can also be an important communication barrier during environmental emergencies, for which outreach through internet sources can be a key strategy for public health officials (Houston et al., 2015; Jha et al., 2016; Nguyen et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2017).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percent of population aged 65 and older

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

Adults aged 65 and older face higher rates of social isolation than the general population, which can affect their ability to affect change or influence environmental decision-making in their communities (Andrew & Keefe, 2014). Additionally, older populations may be more susceptible to environmental pollution due to lowered immune function and accumulated oxidative stress associated with a lifetime of exposures (Cakmak et al., 2007; Hong, 2013; Morello-Frosch et al., 2011).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percent of population aged 17 and younger

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

Persons below voting age have a limited ability to influence environmental decision-making as well as limited resources, knowledge, or life experiences necessary to affect change (Flanagan et al., 2011). Additionally, children are particularly susceptible to negative health effects associated with a range of environmental pollution due to a combination of physiological sensitivity and behaviors that put them at greater risk (Morello-Frosch et al., 2011). Physiological factors, such as rates of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of chemicals, make children more vulnerable to environmental pollution than adults (Faustman et al., 2000).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percent of civilian, noninstitutionalized population with a disability

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

Those living with a disability may experience social or physiological barriers to full participation in the environmental decision-making process. Persons with disabilities are often disproportionately affected at every stage of disaster events and disaster recovery (Chakraborty et al., 2019; Peek & Stough, 2010). Furthermore, certain types of disability are associated with increased physiological susceptibility to environmental pollution, particularly PM2.5 and other forms of air pollution (Dales & Cakmak, 2016; H. Lin et al., 2017; Weuve et al., 2016).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percent of persons (age 5 and older) who speak English “less than well”

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

The ability to communicate in English can be an important factor in determining a community’s ability to participate in civil discourse surrounding environmental decision-making. Documents and news sources covering environmental issues are often not available in languages other than English, hampering non-English speakers’ ability to inform themselves and engage in these issues (Teron, 2016). Furthermore, discrimination against non-English speakers can lead to exclusion from decision making and is correlated with increased stress and reduced quality of life (Gee & Ponce, 2010). Non-English speakers may also be more vulnerable during disasters or extreme climate events if materials aimed at dissemination of emergency information are available only in English (Nepal et al., 2012; White-Newsome et al., 2009).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percentage of persons living in group quarters (includes college residence halls, residential treatment centers, group homes, military barracks, correctional facilities, and worker’s dormitories)

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

Institutionalized persons, those in correctional facilities, nursing homes, and mental hospitals, are particularly vulnerable to environmental injustice and often have limited ability to influence environmental decision-making. For example, persons who are incarcerated or detained often face disproportionate exposures to environmental contaminants due to poor institutional conditions, exposures through hazardous work programs, and a lack of social capital to improve conditions for themselves (Pellow, 2021). Persons institutionalized in nursing homes or mental hospitals face similar issues of autonomy and lack of social capital or physical ability to influence environmental decision-making. Furthermore, persons in institutional facilities are often neglected in environmental decision making and hazard response (Cutter, 2012).

Non-institutionalized persons living in group quarters are also vulnerable to environmental injustice, though perhaps not as clearly as institutionalized persons. Military bases share some characteristics with correctional facilities in that they are often sites of concentrated environmental contamination and many of their residents come from similar socioeconomic backgrounds and have similarly little influence over the day to day operations that result in contamination (Broomandi et al., 2020). People living in group homes, missions, and shelters may have limited legal status, limited time, and limited resources, and thus diminished ability to influence environmental decision-making (Goodling, 2020).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percentage of total housing units designated as mobile homes

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

Mobile homes are often clustered in communities confined to low-value areas due to zoning laws and stigma (Maantay, 2002). Mobile homes are also often inhabited by farm workers, who are beholden to landowners for environmental decision-making such as use of agricultural pesticides (Early et al., 2006). These aspects of stigma, zoning, and lack of land ownership can inhibit these populations’ ability to influence local environmental policy. Furthermore, issues of poor construction and energy inefficiency can render residents of mobile homes more susceptible to negative health effects associated with air pollution (MacTavish et al., 2006) and extreme heat (Phillips et al., 2021), while observed unreliability of access to drinking water poses further risks to residents’ health (Pierce & Jimenez, 2015).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Environmental Burden Module

Indicator: Mean annual number of days with maximum 8-hour average ozone concentration over the National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS), averaged over three years (2014-2016)

Data Year: 2014-2016

Data source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Air Quality System (AQS; combined monitoring and modeled data)

Rationale:

Both acute and long-term exposure to elevated levels of ozone in air are associated with negative health effects ranging from increased morbidity and mortality due to respiratory and cardiovascular disease (Crouse et al., 2015; Last et al., 2017). Together with PM2.5, ozone is a major contributor to air pollution-related morbidity and mortality, with an estimated 4,700 ozone-related deaths in the United States in 2005 (Fann et al., 2012).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Mean annual percent of days with daily 24-hour average PM2.5 concentrations over the National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS), averaged over three years (2014-2016)

Data Year: 2014-2016

Data source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Air Quality System (AQS; combined monitoring and modeled data)

Rationale:

Inhalation of particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 microns or less (PM2.5) can have a number of adverse effects on health and well-being. Acute exposure to elevated levels of PM2.5 can lead to irritation of eyes, nose, throat and lungs , and increases relative risk of acute cardiovascular events including admission to a hospital for stoke (Rajagopalan et al., 2018). Long-term exposure to elevated levels of PM2.5 is associated with higher rates of mortality from a number of conditions ranging from cancer to cardiopulmonary disease (Dockery & Pope, 1994). In the U.S. in 2005, an estimated 130,000 deaths were attributable to PM2.5-related causes (Fann et al., 2012).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Diesel particulate matter concentrations in air, μg/m3

Data Year: 2014

Data source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency National Air Toxics Assessment (NATA: modeled data)

Rationale:

Diesel particulate matter (DPM) is a particle emission from a diesel motor made of an elemental carbon core and various adsorbed organics compounds and other chemical components (Wichmann, 2007). Evidence indicates that DPM exposure may cause respiratory symptoms via inflammation and oxidative stress (Ristovski et al., 2012). Acute exposure to DPM has been associated with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and other cardiovascular issues (Peters et al., 2001) and DPM contains carcinogens such as benzene and formaldehyde that may lead to the development of certain kinds of cancer (Krivoshto et al., 2008).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Lifetime cancer risk from inhalation of air toxics

Data Year: 2014

Data source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency National Air Toxics Assessment (NATA; modeled data)

Rationale:

Air toxics cancer risk is a composite measure assessing the cancer risk associated with inhaling 140 different hazardous air pollutants (HAPs). HAPs such as benzene, dioxin, formaldehyde, and ethylene oxide are known carcinogens which, at various concentrations, contribute to lifetime risk of developing certain types of cancer (Loh et al., 2007; Reynolds et al., 2003; Whitworth et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2009). The cancer risks estimated by NATA are based on modeled exposure concentrations, assessments of each pollutant’s unit risk estimate, and inhalation reference concentration. It is important to note that diesel particulate matter (DPM), which is another CDC/ATSDR EJI indicator, is one of the HAPs included in the 2014 NATA lifetime cancer risk model. However, the DPM indicator is represented as distinct from the air toxics cancer risk indicator because DPM is only one of the 140 HAPs used to create the 2014 NATA lifetime cancer risk estimate and is associated with many health issues other than cancer. For more information on the 2014 NATA, including a full list of HAPs included in the lifetime cancer risk model, please visit https://www.epa.gov/national-air-toxics-assessment/2014-nata-assessment-results.

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Proportion of tract area within 1-mi buffer of EPA National Priority List (NPL) sites

Data Year: 2021

Data source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Facility Registry Service (FRS)

Rationale:

Sites on the EPA’s National Priorities List (NPL), which are designated by the U.S. EPA as priorities through hazard assessment, nomination by states or territories, or issuance of a health advisory by the Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry, can present several potential hazards to the health and well-being of neighboring communities. While actual risks to health vary by sites, proximity to these sites can have important and complex effects on community stress and perceptions of risk (Kiel & Zabel, 2001; Pearsall, 2010). Furthermore, legacy contaminants associated with many of these sites can affect multiple environmental media, becoming airborne with windblown dust or leaching into soil and groundwater and possibly exposing surrounding communities through drinking water or vapor intrusion.

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Proportion of tract area within 1-mi buffer of Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) sites

Data Year: 2021

Data source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Facility Registry Service (FRS)

Rationale:

Sites listed through the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) include all facilities with 10 or more full time employees which operate within certain industrial sectors and annually either 1) manufacture more than 25,000 pounds of listed chemicals or 2) used more than 10,000 pounds of listed chemicals. These sites can affect the health of neighboring communities through routine chemical releases into air, soil, or water. Residential proximity to TRI sites has been linked to higher rates of hospitalization for COPD (Brown-Amilian & Akolade, 2021) as well as increased risks for certain kinds of cancer (Bulka et al., 2016). Additionally, TRI sites and other noxious and unwanted land uses can produce noise and odor pollution and, particularly in communities burdened by multiple such land uses, can lead to increased burden of community stress (Wilson et al., 2012).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Proportion of tract area within 1-mi buffer of EPA Treatment, Storage, and Disposal Facilities (TSDF)

Data Year: 2021

Data source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Facility Registry Service (FRS)

Rationale:

Sites listed as Treatment, Storage, and Disposal Facilities (TSDF) are responsible for handling hazardous wastes such as manufacturing by-products, cleaning fluids, or pesticides throughout the process of collection, transfer, and ultimately disposal. Volatile substances generated by waste may become aerosolized or migrate into soil and water, leading to vapor intrusion or contamination of groundwater (Johnston & MacDonald Gibson, 2015; Marshall et al., 1993). Proximity to hazardous waste sites has been linked to increased rates of hospitalizations for diseases such as stroke, diabetes, and coronary heart disease (Kouznetsova et al., 2007; Sergeev & Carpenter, 2005; Shcherbatykh et al., 2005).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Proportion of tract area within 1-mi buffer of EPA Risk Management Plan (RMP) sites

Data Year: 2021

Data source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Facility Registry Service (FRS)

Rationale:

The EPA’s Risk Management Plan (RMP) program covers ~12,500 of the nation’s most high-risk facilities that produce, use, or store significant amounts of certain highly toxic or flammable chemicals. These facilities must prepare plans for responding to a worst-case incident such as a major fire or explosion that releases a toxic chemical into the surrounding community (US Environmental Protection Agency, 2016). There are many negative health effects associated with residing in proximity to RMP sites. The EPA estimates that about 150 “reportable” incidents of unplanned chemical releases occur each year at RMP facilities, separate from the daily toxic emissions that are allowed under most operating permits. The EPA notes that these incidents “pose a risk to neighboring communities and workers because they result in fatalities, injuries, significant property damage, evacuations, sheltering in place, or environmental damage” (US Environmental Protection Agency, 2021). Besides direct deaths and injuries caused by chemical release and explosion incidents, research shows increased risk of cancer and respiratory illness from toxic air pollution exposure at these sites. Although the effects of proximity to RMP sites on community stress has not formally been assessed, it is also reasonable to assume that fear of potential chemical plant disasters contributes to the burden of psychosocial stress imposed on communities by cumulative environmental and social stressors (Hynes & Lopez, 2007).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Proportion of tract area within 1-mi buffer of a coal mine

Data Year: 2021

Data source: U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration Mine Data Retrieval System (MDRS)

Rationale:

Coal mining, while on the decline in the United States, is still of substantial concern for the health of exposed communities, including both traditional underground mining methods and surface mining methods, such as mountaintop removal (MTR). Studies have observed elevated blood inflammation levels, increased cardiopulmonary, lung, and kidney disease, and increased rates of lung cancer mortality in heavy Appalachian coal mining communities as a result of air pollution from mining activity (Hendryx et al., 2010; Hendryx & Ahern, 2008; Hendryx & Luo, 2015). Proximity to MTR sites has been linked to impaired respiratory health, including increased occurrence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)(Hendryx & Luo, 2015) and may predict increased risk for depressive and substance use disorders (Canu et al., 2017). Air pollution from coal mining has also been connected to adverse effects in-utero for pregnant women, including low-birthweight (Ahern et al., 2011). Exposure pathways to coal contamination are also multifactorial. Coal slurry (the practice of disposing liquified coal wastes underground) can leach coal-related pollutants into well and ground water, potential drinking water sources for residents (Ducatman et al., 2010).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Proportion of tract area within 1-mi buffer of an active lead mine

Data Year: 2021

Data source: U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration Mine Data Retrieval System (MDRS)

Rationale:

Lead mines constitute an important health risk for surrounding communities. Studies in the U.S. have suggested that soil and dust contaminated from lead mining as well as other waste-byproducts of mining pose a health hazard to nearby communities, particularly to children (Malcoe et al., 2002; Murgueytio et al., 1998). Studies outside of the U.S. evaluating health risks associated with communities in close proximity to active lead mines have found evidence of elevated blood lead levels in children (Schirnding et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2012).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Proportion of tract area not within 1-mi buffer of a park, recreational area, or public forest

Data Year: 2020

Data source: TomTom MultiNet® Enterprise Dataset

Rationale:

Parks and greenspaces represent important healthy features of the built environment, providing spaces for physical recreation and promoting physical activity (Bedimo-Rung et al., 2005; Cohen et al., 2007), though evidence that parks promote physical activity in rural areas is mixed (Reuben et al., 2020; Roemmich et al., 2018). Parks and greenspaces also play an important role in mitigating urban heat island effects (P. Lin et al., 2017; Shishegar, 2014) and can offer refuge on extreme heat days (Brown et al., 2015; Voelkel et al., 2018). Proximity and access to parks and greenspaces can also have important implications for mental health, with studies indicating that measures of proximity and access to these spaces are associated with better overall mental health (Bojorquez & Ojeda-Revah, 2018; Sturm & Cohen, 2014; Wood et al., 2017). While park design quality, and neighborhood perceptions of safety can have important mediating effects on these benefits (Cohen et al., 2010; Cutts et al., 2009; Rigolon et al., 2018), and while there are concerns associated with “greening” and gentrification (Mullenbach & Baker, 2020; Wolch et al., 2014), these spaces nearly always provide an overall benefit to neighboring communities and lack of access constitutes an important issue for health and environmental justice (Boone et al., 2009; Jennings et al., 2012; Rigolon, 2017; Rigolon et al., 2018).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Proportion of occupied housing units built prior to 1980

Data Year: 2015-2019

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS)

Rationale:

Age of housing units has important implications for potential exposure to lead. While lead-based paint was banned in 1978, housing built around that time or prior often contain underlying layers of lead-based paint. While underlying layers of lead-based paint do not necessarily constitute a health risk, chipping or flaking that exposes underlying layers of lead-based paints may lead to ingestion by children (Lanphear et al., 1996). Measures of housing built prior to the ban on lead-based paint have repeatedly been identified as one of the leading predictors of blood-lead levels in children (Kim et al., 2002; Sadler et al., 2017; Schultz et al., 2017). There are no known safe levels of lead exposure, especially among children, who are highly susceptible to neurological and developmental issues associated with lead exposure.

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: National Walkability Index Score

Data Year: 2021

Data source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency National Walkability Index

Rationale:

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers walkability as ‘the idea of quantifying the safety and desirability of the walking routes’ (Smith, 2015). This conceptualization of walkability, stemming from the scientific evidence that walking can boost metabolism, lower blood sugar and improve mental health (Barton et al., 2009), has become a quantifiable variable to study health-promoting effects of the built environment. Research shows that nearby available locations for walking and biking promote physical activity. Higher residential neighborhood walkability has been associated with more walking, higher overall physical activity, lower body mass index (BMI), lower incidence of diabetes, improved glycemic control among residents, and lower premature mortality (Awuor & Melles, 2019; Chen & Kwan, 2015; L. Frank et al., 2010; L. D. Frank et al., 2004, 2005, 2006; Freeman et al., 2013; Hirsch et al., 2014; US Environmental Protection Agency, 2014, 2017). Measures of neighborhood walkability that include measures of street connectivity, transit stop density, and land use mix, all features of the EPA’s National Walkability Index, have also been shown to be positively associated with various measures of accessibility for older adults and persons with disabilities (King et al., 2011; Kwon & Akar, 2022; Mahmood et al., 2020). While it is important to note that the associations between built environment measures of walkability on health may be different in rural and urban neighborhoods (Stowe et al., 2019), and while these measures may not account for physical or social factors that could mediate the effects of walkability on physical activity and health benefits (Bracy et al., 2014; Forsyth, 2015), walkability nevertheless constitutes an important environmental amenity.

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Proportion of tract area within 1-mi buffer of a high-volume street or road

Data Year: 2020

Data source: TomTom MultiNet® Enterprise Dataset

Rationale:

High-volume roads, such as interstate highways, can constitute major hazards to surrounding communities. Vehicular emissions are a major source of air pollutants such as ozone and diesel particulate matter, and proximity to busy roads has been associated with a number of adverse respiratory symptoms, childhood cancers, adverse birth outcomes, and overall mortality (Boothe & Shendell, 2008). Water runoff from roads can also lead to deposition of heavy metals and other pollutants in nearby soils and waters (Khalid et al., 2018; Sutherland & Tolosa, 2001). Noise pollution associated with traffic is also associated with significant increases in community stress (Barbaresco et al., 2019) and can lead to elevated risk of cardiovascular disease (Münzel et al., 2021) and adverse mental health outcomes (Díaz et al., 2020).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator details: Proportion of tract area within 1-mi buffer of a railway

Data Year: 2020

Data source: TomTom MultiNet® Enterprise Dataset

Rationale:

Like roads, railways can also present a significant source of noise pollution to nearby communities. This noise pollution can constitute a major annoyance and source of community stress, especially when combined with noise pollution from traffic (Öhrström et al., 2007). Among all transportation-associated sources of noise pollution, railway noise is associated with the most significant levels of sleep disruption and associated increases in stress and diastolic blood pressure (Elmenhorst et al., 2019; Petri et al., 2021).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Proportion of tract area within 1-mi buffer of an airport

Data Year: 2020

Data source: TomTom MultiNet® Enterprise Dataset

Rationale:

Airports are important sources of noise pollution. Studies indicate that noise pollution associated with residential proximity to airports can constitute a significant nuisance, and can lead to elevated levels of stress and sleep disturbance (Elmenhorst et al., 2019; Ogneva-Himmelberger & Cooperman, 2010; Ozkurt et al., 2015). Airports are also important sources of air, soil, and groundwater contamination. Accidental releases from leaky storage tanks, use of hazardous chemicals in rescue and firefighting training, and stormwater runoff all contribute to infiltration of chemicals such as benzene, trichloroethylene, carbon tetrachloride, and a range of perfluorochemicals into soil and groundwater (Nunes et al., 2011).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Percent of tract watershed area classified as impaired

Data Year: 2019

Data source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Watershed Index Online (WSIO)

Rationale:

Surface waters such as rivers and lakes are important for recreation and fishing, and impairment of these waters can constitute a potential nuisance or even hazard to nearby residents. Waters may be classified as impaired due to elevated levels of waterborne pathogens or significant contamination by toxic substances. Waterborne pathogens can pose a significant health risk through recreational exposure (McKee & Cruz, 2021), while ingestion of fish from chemically-impaired waters can be a significant exposure pathway for a number of pollutants that bioaccumulate in tissues (Dórea, 2008).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Health Vulnerability Module

Indicator: Estimated prevalence of asthma among adults 18 and older greater than for 66.66% of U.S. census tracts (2020)

Data Year: 2020

Data source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention PLACES Estimates

Rationale:

Outdoor air pollution is associated with increases in asthma attacks (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; Peel et al., 2005) and asthma-related ED visits (Norris et al., 1999; Slaughter et al., 2005; Stieb et al., 1996; P. E. Tolbert et al., 2000; Villeneuve et al., 2007). Inhalation of pollutants such as PM2.5, ozone, and diesel particulate matter can lead to oxidative stress which inflames the airways and exacerbates asthma symptoms, and both acute and long-term exposure to asthma are associated with worsening asthma symptoms (Guarnieri & Balmes, 2014).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Estimated prevalence of all-cause cancer (excluding skin cancer) among adults 18 and older greater than for 66.66% of U.S. census tracts (2020)

Data Year: 2020

Data source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention PLACES Estimates

Rationale:

Increases in PM2.5 are also associated with increased all-cause mortality for young adult cancer patients diagnosed with all cancer types (Ou et al., 2020). Long-term exposure to PM2.5, ozone, and other air pollutants is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in persons diagnosed with cancer, including lung cancer (Jerrett et al., 2013; Pope III et al., 2002), liver cancer (Deng et al., 2017), pediatric lymphomas, and CNS tumors (Ou et al., 2020). Experimental research suggests that intermediate to long-term exposure to both fine and coarse particulate matter may accelerate oncogenesis (the formation of tumors) and cause increased expression of inflammation and oncogenesis-related genes in rat brains (Ljubimova et al., 2018).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Estimated prevalence of high blood pressure among adults ≥ 18 greater than for 66.66% of U.S. census tracts (2020)

Data Year: 2020

Data source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention PLACES Estimates

Rationale:

Elevated levels of ambient PM2.5, ozone, and other air pollutants are associated with the increased prevalence and elevated risk of adverse health outcomes like heart attack and overall increases in blood pressure, including hypertension (Coogan et al., 2012; Giorgini et al., 2016; Lee, 2020). Long-term exposure to particulate matter, other traffic-related air pollution, and traffic noise pollution have been associated with increased blood pressure and a higher risk of developing hypertension (Dong et al., 2013; Foraster et al., 2014; Fuks et al., 2014). Hypertension is an established risk factor for a number of negative cardiovascular health outcomes, including coronary heart disease and stroke, but cardiovascular complications related to high blood pressure can occur before the onset of established hypertension (Go et al., 2013).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Estimated prevalence of diabetes among adults 18 and older greater than for 66.66% of U.S. census tracts (2020)

Data Year: 2020

Data source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention PLACES Estimates

Rationale:

Research suggests that air pollution, such as PM2.5, can cause oxidative stress and inflammation, leading to impairments in insulin signaling associated with diabetes (Meo et al., 2015). PM2.5 is also associated with markers of systemic inflammation in individuals with diabetes (Dubowsky et al., 2006), which may lead to greater risk of diabetes-related negative health outcomes. Proximity to hazardous sites and land use have also been associated with increased risk of hospitalization among individuals with diabetes (Kouznetsova et al., 2007).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

Indicator: Estimated prevalence of poor mental health for ≥ 14 days among adults 18 and older greater than for 66.66% of U.S. census tracts (2020)

Time Period: 2020

Data source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention PLACES Estimates

Rationale:

Poor mental health can be both caused by and exacerbated by negative environmental quality. One study found that residential proximity to industrial activity negatively impacts mental health directly and by mediating individual’s perceptions of neighborhood disorder and personal powerlessness, with these effects being most prominent in racial/ ethnic minority populations and populations in poverty (Downey & Van Willigen, 2005). Another exploratory study in the U.S. found a strong positive link between exposure to environmental pollution and an increase of prevalence in psychiatric disorders in affected patients (Khan et al., 2019). Poor environmental quality may also affect the quality of life (i.e. the expectation and concern for one’s own health and life) negatively through the mediating effects of increased stress and poor sleep (Chang et al., 2020).

For more information on indicator calculation and for a full list of references, please view Technical Documentation for the Environmental Justice Index 2022.

[PDF - 702 KB]

[PDF - 702 KB]For more information, contact the EJI Coordinator at eji_coordinator@cdc.gov.

Media inquiries may be sent to placeandhealth@cdc.gov.

Suggested citation: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Agency for Toxic Substances Disease Registry. 2022 Environmental Justice Index. Accessed [Date]. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/eji/index.html